In Marx’s Republic

By Daniel Luban / The Nation

5 أبريل 2018

Was Karl Marx a political thinker? It might seem like an odd question: What else would he be? Yet over the course of the 20th century, the answer came to seem less clear. Within a few years of the Russian Revolution, Carl Schmitt was already depicting Marxism as generically similar to liberalism, a form of “economic thinking” hostile to all genuine politics. Bolsheviks and American financiers shared the ideal of an “electrified earth,” Schmitt asserted, differing “only on the correct method of electrification.” At the height of the Cold War, Hannah Arendt would describe Marx’s work as marking the “end” of a tradition of political thought that had started with Socrates. And Sheldon Wolin would see in Marx the most powerful expression of the 19th century’s “contempt for politics.” Marx’s thought looked less like a diagnosis of modern society’s ills than a symptom of them.

This line of thinking drew much of its appeal from developments on the world stage: Even in its less sanguinary moments, actually existing socialism seemed to offer little more than dreary technocracy. Its appeal also owed something to developments within the academy: As universities expanded and disciplines solidified, political thought found itself pushed to the margins of an increasingly quantitative social-science universe, threatened by ascendant competitors like economics and sociology. A natural line of defense was to stake out some distinct domain called “the political,” the autonomy of which must be guarded against any trespass. Opinions differed as to what constituted distinctly political concepts: Friend and enemy, speech and action, power, violence, legitimacy, and authority were all put forward as candidates. But thinkers in this vein could agree that politics itself was threatened by the encroaching forces of economy and society, and that liberalism and Marxism were both complicit in the problem.

The notion that Marxism was hostile to politics wasn’t entirely a 20th-century imposition, for the master’s own writings offered some warrant for concern. The canonical Marxist statements here actually came from Engels, whose Anti-Dühring prophesied the withering away of the state and the replacement of “the government of persons” by “the administration of things.” But Engels was simply drawing out an argument that he and Marx had been making since The Communist Manifesto, where they described “political power” as “merely the organized power of one class for oppressing another.” When Marx speaks of politics, he means the state and its coercive machinery, deployed in support of a given class hierarchy. Hence a world without classes would be one without states, and ultimately one without politics. “Public power” will remain under communism, the Manifesto tells us, but it will have lost “its political character.”

One plausible response would be to insist on a more expansive understanding of politics. Stop worrying about defending the autonomy of the political from other domains, and the forms of politics that underlie every domain of human life will come into view. Stop defining politics solely in terms of the coercive machinery of the state, and the “public power” that remains under communism will become visible as a form of politics in its own right.

Yet this response, however reasonable, can also be misleading, for it implies that the place to look for Marx’s politics is in his vision for a postcapitalist society. For obvious reasons, Marx’s notoriously brief and scattered writings on this subject have attracted outsize interest, but that hardly means that they represent the most valuable or most original part of his political thinking. His predictions about the death of the state, for instance, were a commonplace among 19th-century radicals rather than a distinctive feature of his thought. So was his broader hope for a world after politics, in which coercion would no longer be necessary to maintain the hierarchies of a deformed social order—an echo of the much older Christian view that saw political power as a punishment for original sin that would vanish in the world to come.

The most important question, however, is not whether politics will last forever, but rather what it will look like in the meantime. And so the place to look for Marx’s politics is not in his vague intimations about the future, but in his analysis of “all hitherto existing society”; not in his sketches of life after capitalism, but in his depiction of life under it.

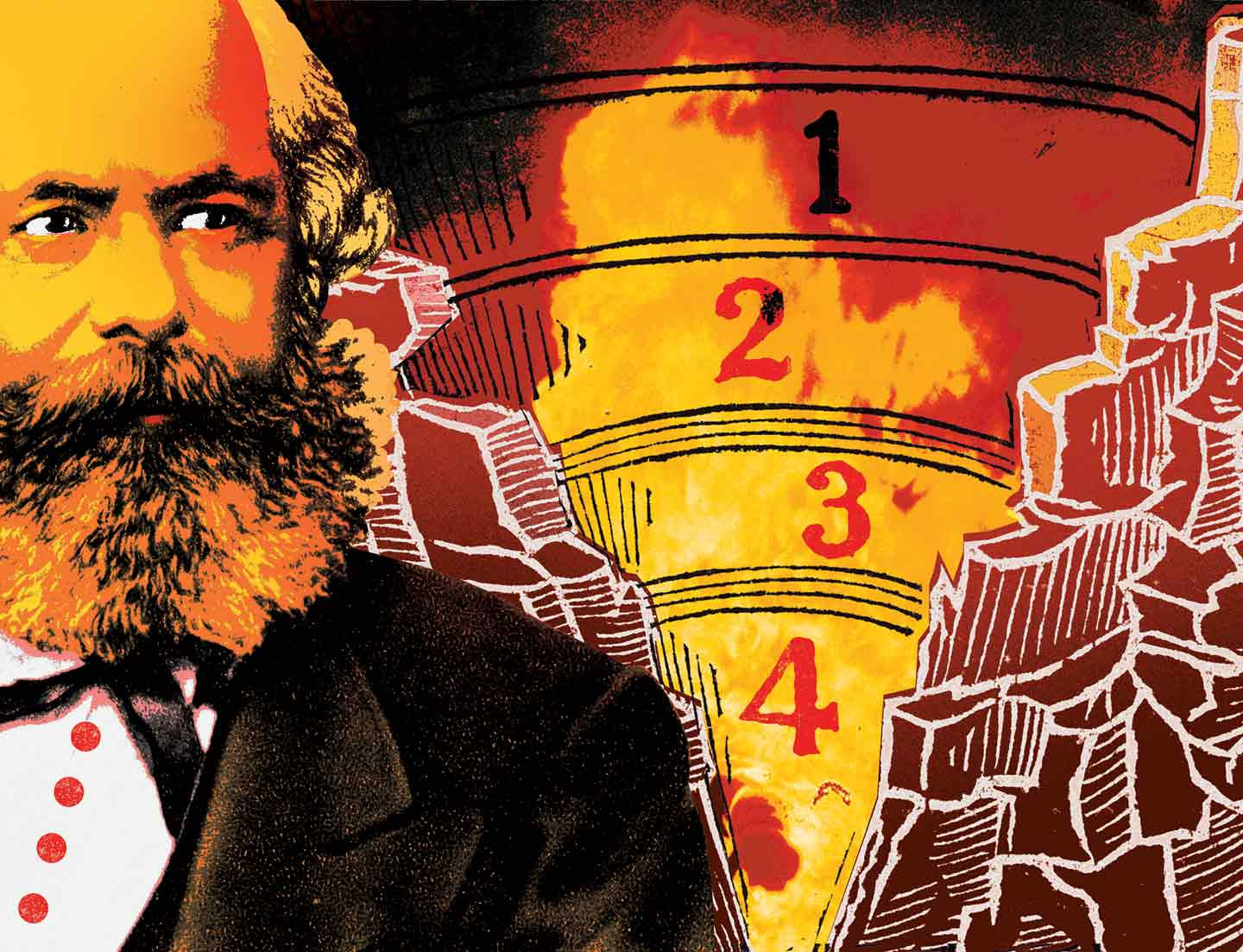

Something like this intuition is at the center of William Clare Roberts’s new book Marx’s Inferno, the most substantial treatment of Marx’s political theory in recent years. Roberts does have some interesting things to say about Marx’s vision for a postcapitalist society. But he rightly locates the core of Marx’s politics in its diagnosis of capitalism, which he analyzes through an imaginative and carefully argued reading of Marx’s 1867 masterpiece, Capital.

This choice of focus is more counterintuitive than we might think. After all, the book that appeared in 1867 was billed as the first volume of a projected trilogy (and hence is typically called Capital, Volume I). It was only quite late in the writing process that Marx scrapped his original plans to publish the entire work simultaneously; even as he completed the first volume, he was still promising to finish the final two within a year. That proved to be wildly optimistic: Beset by the financial and health problems that would dog him throughout his life, Marx never completed the rest of the project. The books that would appear as Capital’s final two volumes were pieced together by Engels from Marx’s notes after his death.

This might suggest that the project of Capital was an unfinished one, perhaps even a failed one. Thus, later interpreters have often gravitated to Marx’s earlier, long-unpublished writings—ranging from the Paris manuscripts of 1844 to the so-called Grundrisse that he abandoned in 1858—hoping to recover core intuitions that were lost when Marx got bogged down in Capital. At the very least, the checkered history of Capital’s composition might cut against the notion that Volume I forms a coherent whole. Thus, influential interpreters like David Harvey and Michael Heinrich insist on the need to analyze all three volumes as a unit (however fragmentary the latter two might be). Other interpreters, confronted with the patchwork quality of Volume I, lop off those pieces that they find extraneous, whether it’s the abstract analysis of the commodity form at the beginning or the historical account of “primitive accumulation” at the end.

Roberts, by contrast, treats Volume I as the authoritative distillation of Marx’s political theory, his “premier act of political speech.” He justifies this partly by the very fact of its publication: To prioritize Marx’s unpublished manuscripts and discarded drafts over the book that he was willing to present to the world is to reverse Marx’s own judgments about what was valuable in his work. But Roberts’s larger and more ambitious argument is that Marx’s readers have missed the underlying structure and coherence of Volume I itself.

Roberts’s title refers to the book’s most attention-grabbing argument: that Marx modeled the structure of Volume I on Dante’s Inferno, which he recast “as a descent into the modern ‘social Hell’ of the capitalist mode of production,” with himself in the role of “a Virgil for the proletariat.” Marx unquestionably made allusions to Dante in the work, and he also made use of the “social Hell” trope that was common among the socialists of his day, but Roberts argues that the parallels run much deeper than that. Dante divided his Hell into four regions, each housing a particular set of sinners; so too can Marx’s seemingly disjointed discussion be cut into four main parts, replicating Dante’s descent through the realms of incontinence, violence, fraud, and treachery. The Hell here is not (or not just) capitalism itself but also its theoretical counterpart, bourgeois political economy. Just as Dante had to pass through Hell on his journey to Paradise, Marx seeks to demonstrate “the necessity of going through political economy in order to get beyond it.”

Drawing the parallel between the two books so tightly requires a great deal of fine—and perhaps overfine—argumentation, and some readers (this one included) may ultimately remain unconvinced, but Roberts’s deeper interpretive claims do not depend on the Inferno/Capital correspondence. Some of his most interesting arguments relate to the audience for whom he suggests Capital was intended: fellow socialists and comrades in the workers’ movement, whom Marx hoped to wean off rival versions of radicalism associated with figures like Proudhon, Robert Owen, and Saint-Simon. Whether a 1,000-page treatise was the best way to do this is a question that Roberts doesn’t raise. (It was the long-suffering Engels who first managed to put Marxist ideas into a form that workers actually wanted to read, for his troubles earning the contempt of posterity as a shallow vulgarizer.) Regardless, Roberts effectively shows how Marx made use of the ambient language of 19th-century radicalism, as well as how he moved beyond it.

This sort of historical contextualization is the most well-trodden part of the book’s argument. But treatments of the subject tend to restrict themselves to Marx’s many explicit polemics against his rivals; Roberts goes further in making a strong case that such concerns are embedded in surprising ways in Capital itself. And while contextualization is often meant as a deflationary move—for example, in the recent Marx biographies by Gareth Stedman Jones and Jonathan Sperber, both of which cast him as a 19th-century figure with limited relevance for the 21st—Roberts’s aims are quite the opposite. By examining Marx’s historical reference points, he suggests, we will see that they have “more potent and varied contemporary analogues” than we might otherwise think. In short, understanding Marx in the context of his times shows him to be more rather than less relevant to our own.

The main thrust of Marx’s break from other strands of socialism, Roberts argues, is to “de-personalize and de-moralize” their critique of capitalism. Instead of tracing the system’s ills to the immorality of individual capitalists, Marx wants to show how capitalism’s logic dictates the behavior of all parties within the system, capitalists very much included. Likewise, while other radicals imagined a fundamentally healthy process of exchange that was distorted by the intrusion of some alien element—whether the introduction of money, the persistence of feudal hierarchy, or the prevalence of force and fraud—Marx denies that we can isolate any such discrete factor as the root of all evil. Capitalism is modern, it is coherent, and it is systematic; its opponents must therefore resist the easy moralism that attributes its ills to individual miscreants and individual acts of injustice.

To say that Marx rejects this kind of moralism, however, is not to say that he lacks moral convictions of his own. His belief that capitalism is unstable is inseparable from his belief that it is unjust. In fact, Roberts argues, we can be more specific about the content of Marx’s political morality: At bottom, he is what contemporary political theorists would call a “republican,” for whom the primary goal of politics is to prevent the domination of some human beings by others. Yet the systematic nature of capitalist domination demands an equally systematic response, and so Marx rejects separatist fantasies of carving out independent spaces within capitalism. Instead, what he envisions is something that Roberts calls a “republic without independence.” Although Roberts does not specify precisely what this would involve, he suggests that it would be something like “a global system of interdependent cooperatives managing all production by nested communal deliberation,” a scaling-up for a global age of the cooperatives envisioned by the utopian socialist Robert Owen.

What does it mean to call Marx a “republican”? Traditionally, the term would refer to critics of monarchy or empire, but what Roberts has in mind is more specific: It means that the primary value in Marx’s system is ensuring the absence of domination. “Domination” is itself a tricky word. We often use it loosely to refer to any large imbalance of power (as when we say that the Celtics dominated the Knicks). But as defined by prominent neo-republicans like Philip Pettit and Quentin Skinner, “domination” means being at the mercy of the arbitrary will of another, regardless of whether this will is actually exerted. The canonical example is the slave subject to the whims of a master, a vulnerability that remains constant whether or not the master chooses to exercise his power. (What connects this view historically to republicanism in the more familiar sense is that many saw the power of absolute monarchs as analogous in this way to that of the slave master.)

In Pettit’s language, republican freedom is therefore a kind of “social freedom.” We are free when other people do not dominate us, and although domination can take place between groups as well as individuals, it remains the case that republicanism is exclusively concerned with relationships between human beings. Someone trapped beneath a boulder is not unfree in the relevant sense; poverty or disability might constrain or thwart our plans, but they only count as unfreedom insofar as they are connected to interpersonal domination.

Thus, the political thrust of republicanism is to remove the element of arbitrary will from human social life. Human beings will necessarily remain subject to social forces outside their control, but these forces should be rendered as impersonal—as nonarbitrary—as possible. State power can therefore appear unobjectionable if it is constrained by the rule of law; as Friedrich Hayek (in this respect a kind of republican) put it, so long as the laws of the state “are not aimed at me personally but are so framed as to apply equally to all people in similar circumstances, they are no different from any of the natural obstacles that affect my plans.” More important for our purposes, market forces are only objectionable to a republican to the extent that they are sources of domination, and they cannot be considered sources of domination if they are genuinely impersonal.

Of course, there are various ways in which economic life does produce domination in this sense, creating new forms of dependence and arbitrary power. We might think of the power exercised by employers within the workplace, a form of arbitrary rule emphasized historically by so-called “labor republicans” and more recently by authors like Elizabeth Anderson. We might equally think of the power exercised within a household by the breadwinner over dependent unwaged workers (typically not a point of emphasis for such labor republicans). And we might think of the broader ways in which the inequalities produced by markets empower entire classes of people over others. Marx was certainly well aware of many of these forms of domination characteristic of capitalism—and if that, for Marx, was all that capitalism is, then we might describe his critique as republican.

But Marx saw something else in capitalism. It did not just create new masters and confer arbitrary power onto new individuals and classes. It also created new and genuinely lawlike social forces, forces that could be described as neither arbitrary nor willful. Republicans often see market forces as unobjectionable insofar as they come to resemble laws of nature; Marx suggested that this was really coming to pass, as the laws of political economy made themselves felt with the same implacable force as the laws of physics. And although these new laws were ultimately human creations rather than natural facts, they were in their own way impersonal and impartial, imposing themselves on all parties within the system from top to bottom.

Roberts notices this strain in Marx, but sees it as a further extension of the republican conceptual vocabulary: a form of “impersonal domination” in which the capitalist “is as dominated as the wage-laborer.” Yet it’s not clear that this vocabulary can be stretched as far as Roberts suggests. The republican notion of domination can plausibly be extended beyond the state to domains like the firm and the household, and beyond the rule of masters and kings to encompass wider groups of collective perpetrators. But a truly “impersonal domination,” a domination of all human beings alike by lawlike social forces, remains outside the scope of even the most expansive version of republicanism. If Marx believed that capitalism involved a kind of genuinely impersonal unfreedom, this might suggest that he had moved beyond the republican worldview altogether.

There’s another aspect of Marx’s thought that gets lost by assimilating it into republicanism: its deeply material and historical orientation. As a theory of purely social freedom, republicanism tends to abstract from material circumstances and from the relationship between humans and nature. There are cases in which material possibilities can affect domination—a famine, for instance, will tend to increase the dominance of those who control the food supply—but generally speaking, the question of whether people are dominated is independent of how many of them there are, how long they live, what they eat, what tools they use, and so on. Indeed, much of the appeal of republicanism is that its indifference to such questions allows the theory to “travel” easily across history—suggesting that present-day people can hope to be free in the same way that the ancient Romans were, notwithstanding all the other differences separating us from them. Accordingly, Roberts is skeptical of interpretations of Marx that emphasize technological progress and material possibilities, and this skepticism follows from his reading of Marx’s politics.

Yet these were some of Marx’s central concerns. Economistic versions of Marxism may have overemphasized such themes, but it is equally misleading to write them out of Marx altogether. He shows little interest in framing concepts that would apply uniformly across history, or in analyzing social life in abstraction from the material world. Indeed, he sometimes suggests that freedom itself can only be understood with reference to the particular historical stage in which one lives. A famous passage from Capital, Volume III suggests that the “realm of freedom” only begins at the point where labor is no longer required to supply the necessities of human life, and so the extent of freedom varies according to the current state of material and technological progress. In this sense, Marx’s freedom isn’t social freedom at all; it’s the freedom of material beings who are intimately connected to the nonhuman world.

So was Marx a political theorist? If we simply mean that he is a thinker whose work has deep political implications, then the label is unobjectionable. But there are reasons to resist applying the label to Marx’s thinking in anything more than this minimal sense.

Any reader of Capital is bound to notice the wide variety of genres and disciplines that Marx moves across. Some parts are philosophical and some are literary; some seem to be history and others sociology. Most obviously, for a work subtitled “A Critique of Political Economy,” an awful lot of it looks like economics. This might seem less surprising if we recall what Kant and his heirs meant by the term Kritik: not simply a debunking, but an attempt to grasp the limits within which a form of thinking is valid. The problem with bourgeois political economy, understood in this way, is not that its conclusions are entirely wrong (although they sometimes are), but that it mistakes what’s true in specific historical circumstances for what’s universal and natural.

Relatively soon after Capital was published, cracks in its formidable facade began to appear. In the 150 years since, the economists and historians and sociologists and philosophers have all had their say, and they have often suggested that Marx was simply wrong on a variety of points. Orthodox Marxists doggedly set to work defending his doctrines as the straightforward tenets of scientific socialism, but such efforts often seemed to make matters worse. And so, for those caught between these positions, it has been tempting to suggest that both sides have gotten it wrong: that Marx was not an economist or philosopher or historian or all of these at once but something else entirely (say, a “critical social theorist”), whose system floats above such bodies of knowledge and is therefore impervious to their quibbles.

Roberts usefully pushes back against some versions of this view—for instance, from those who want to ignore the historical sections of Capital as irrelevant to the core features of Marx’s core project. At the same time, his version of Marx requires its own set of fire walls: between Volume I and all the other writings, between Marx the theorist and Marx the social scientist. Marx is to be taken as a political theorist and decidedly not as an economist, and as a result his relationship to political economy becomes entirely antagonistic. Marx’s final message to workers, Roberts tells us, is that political economy is merely “the science of their subjection,” and thus that they “need have nothing more to do with this.” A similar injunction seems to hold for us: If Marx is solely critiquing political economy rather than doing it, there’s no point in scrutinizing his account of capitalism as if it were a normal social-scientific theory.

However tempting it might be to see Marx as doing something essentially different from the economists and the historians and all the rest, I don’t think these fire walls can ultimately hold. Not between Volume I and all the other writings—it is surely relevant that Marx aimed to write the final two volumes, and surely relevant that he never managed to—or between Marx the theorist and the various other versions of him that we might discern. He was doing it all, or trying to. Hence his enterprise is vulnerable to attack on any number of fronts, from the grandly philosophical to the hairsplittingly empirical.

The task for readers of Marx today, then, is not to reconstruct a neater and more pristine version of him that will avoid such vulnerabilities, but to decide which parts of his brilliant, sprawling, and monumentally ambitious project we can accept, on the assumption that it certainly won’t be all of it and might not be most of it. Which parts must one accept to be a “Marxist”? That might have been a meaningful question in the days when Marxist parties and regimes bestrode the political landscape, but it seems considerably less meaningful today. Despite the evident nostalgia for old battles between Marxists and anti-Marxists, there is no pressing need at the moment to refight them.

We sometimes ask whether Marx “matters today,” whether he’s “still relevant.” Taking the question at face value, the answer has to be: Yes, he matters, just as everyone else who reorients our ways of thinking matters, above all because the problem of capitalism that he opened up remains central to any attempt to understand the contemporary world. But often the question seems to stand in for another: whether Marx’s thought provides all the resources that we need for this task. This is probably not a useful criterion to apply to any thinker, because it sets a bar that neither he nor anyone else could ever meet. We would do better to emulate Marx’s own attitude toward his predecessors, taking what we can from him without too much agonizing about what we’ve left behind.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018