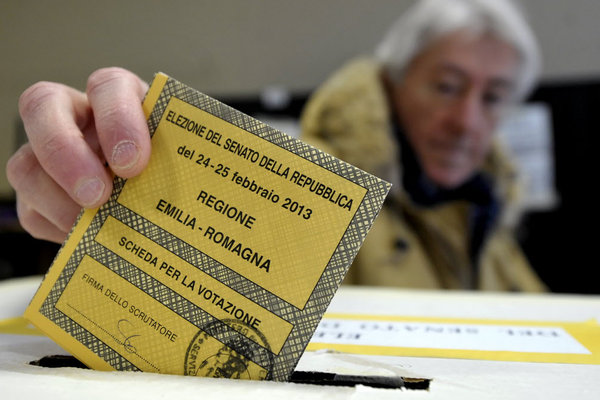

Will voters push Italy across the illiberal Rubicon?

Dominique Moisi/ The Daily Star

7 مارس 2018

In 1841, the Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi completed his celebrated opera Nabucco. “Va, pensiero,” his famous aria describing the fate of the Hebrews in the desert, would go on to become a rallying cry for Italian patriots fighting for liberation from the Austrian Empire.

Then, in a sesquicentenary performance conducted by Riccardo Muti at the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome in 2011, Nabucco was put in the service of democracy. Silvio Berlusconi, the prime minister at the time, was present in the audience, and he would wake up the next day to headlines in the Italian press such as, “Berlusconi Overthrown by Verdi.” Of course, it would be more accurate to say that Berlusconi, who was forced to resign later that year, overthrew himself, through his displays of personal excess and financial corruption.

With Italy approaching decisive parliamentary elections on March 4, such historical references are useful once again. But whereas Italians were mobilizing against Austria in 1841, today they may be heading toward an “Austrian model” of governance by a coalition of the right and the extreme right. And whereas Berlusconi was falling from grace in 2011, he is now a potential kingmaker. At 81, he incarnates an aging and increasingly cynical Italy. Some voters are returning to him out of conviction; others because they fear the alternatives would be even worse.

At the same time, the election’s outcome has been all but impossible to predict, because the process has become so complex that even the most sophisticated voters are having trouble understanding it. Owing to a new electoral law, around 40 percent of parliamentary seats will be decided by first-past-the-post voting, with the rest allocated proportionally.

Still, even if most bets are off, one can reasonably assume two things about this election. First, voter abstention will be high, especially among the young. This is not May 1968, when students across Italy took to the streets. Today, young Italians are deserting the ballot box – though one cannot rule out the possibility that they will eventually return to the streets.

Second, the election will leave Italy divided, not just politically and socially, but also geographically. The populist Five Star Movement (M5S) is particularly strong in the south, the far-right Northern League is powerful in the north, and Venetians are increasingly dreaming about autonomy, or even independence.

Fears that Italy could be returning to the time when it was a mere “geographic expression” are probably overstated. Yet Italy could well reclaim the title of “sick man of Europe” in the weeks to come, especially if the election produces no majority and a hung Parliament. Russia, for its part, would welcome that outcome, and has probably been doing everything it can to bring it about.

An Austrian-style alliance between Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and Matteo Salvini’s Northern League would also bode ill, because it would put Italy at odds with the rest of the European Union’s founding members.

Similarly, a significant victory for M5S would be undesirable. The impulse to reject the status quo is so strong among Italian voters that they have not been deterred by M5S’s failure to govern properly in Rome, where it captured the mayoralty in June 2016. And yet M5S probably cannot achieve a parliamentary majority, and it has vowed not to enter into coalitions with other parties.

The only positive scenario, then, would be an unlikely – but not impossible – alliance between former Prime Minister Matteo Renzi’s center-left Democratic Party and Forza Italia. A coalition government comprising these two parties, would most likely result in Paolo Gentiloni, the well-regarded current prime minister, remaining in power.

That would probably satisfy France and Germany, as well as the European Commission. The main problem, though, is that Renzi has remained unpopular since he resigned as prime minister following a daring but unsuccessful attempt to enact constitutional reforms through a referendum in December 2016.

Despite Italy’s grim economic, social, and political situation – to say nothing of the growing tensions surrounding migration from Northern Africa – financial markets have been relatively serene. Investors do not seem to fear a M5S victory, nor are they particularly concerned that Italy’s youth unemployment is close to 33 percent, or that its rate of economic growth is below the EU average. Are investors underestimating the risk that the EU’s third-largest economy could plunge into a downward spiral into polarization and paralysis?

Whatever the outcome of this uncertain election, it will have far-reaching implications not just for Italy and the EU, but for the cause of democracy worldwide. What kind of Italy will we see after March 4? Will it be one that joins with French President Emmanuel Macron in reinforcing the European project, or will it embrace the authoritarian populism now running rampant in Central Europe? Whether or not they realize it, Italy’s voters are about to choose not just among political parties, but also – and more importantly – between political regimes.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018