The Military-Industrial Complex Is Fundamentally Changing the European Union

Apostolis Fotiadis/The Nation

11 نوفمبر 2017

ith the Eurozone in permanent crisis, Brexit on the horizon, and far-right parties on the rise from Germany to the Czech Republic, the future of the European Union has never seemed so much in doubt. There’s no shortage of leaders aspiring to reboot the unification project that helped Europeans leave behind the terrors of two world wars. But whether it’s the old federalist president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, the solid German Chancellor Angela Merkel, or the maverick French President Emmanuel Macron leading the discussion about Europe’s future, there’s a recurring theme at the top of the priority list: defense.

In his ambitious Sorbonne University speech on the future of Europe in September, Macron expressed his grand vision: “At the beginning of the next decade Europe must have a joint intervention force, a common defense budget and a joint doctrine for action.” This is not merely a political wish list: Both the financing plans and institutional infrastructure for just such a consolidation of European military policy are being put in place at an astonishing speed. Billions of euros have been put on the table for R&D and weapons procurement; plans to militarize development aid, circumvent constitutional restraints, and bring European forces to the battleground are on paper and ready to go. EU members states will meet next Monday in Brussels to sign a defense pact (PESCO-Permanent Structure Co-operation) calling for a massive increase in military investment and to pave the way for the deployment of European forces.

Most European citizens know nothing of these machinations; in the now almost routine panic produced by successive terrorist attacks and declarations of states of emergency by member states, critics’ voices are too marginal to be heard. The emerging alliance between politicians and the EU’s military industries recalls President Eisenhower’s warning almost 60 years ago: “We must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists, and will persist.”

In his emotional State of the Union address in September 2016, EU Commissioner Juncker spoke about the existential threats facing the European “way of life.” In a hostile world, he said, Europe would have to adapt; soft power is no longer enough to confront modern threats: “For European defence to be strong, the European defence industry needs to innovate. That is why we will propose before the end of the year a European Defence Fund, to turbo boost research and innovation.”

The first thing to be turbo-boosted by Juncker’s remarks was EU Commissioner for Industry Elzbieta Bienkowska, who instantly tweeted, “Good news for defence industry: new European Defence Fund before the end of the year!” A year and a half earlier, in March 2015, Bienkowska had initiated a High Level Group of Personalities to advise the European Commission on how to support and promote military and security research, comprising big names from the industry’s and the Commission’s corridors of power. The CEOs of major European military contractors, among them Indra, Saab, Airbus Group, BAE Systems, and Finmeccanica (later renamed Leonardo), were invited to join, alongside think-tank denizens and key political players like the Euro-Atlanticist former Swedish prime minister Carl Bildt and German Member of the European Parliament (MEP) Michael Gahler.

Unsurprisingly, the group’s proposal, delivered in February 2016 to the European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS), put the industry and its favorite interlocutors at the forefront of EU defense policy-making, recommending the establishment of a new military research line in the next EU budget, as well as a dedicated advisory group to support “road-mapping between the industry (the final supplier) and the member states (the trusted customers).” The Commission was advised to consult organizations “like the ASD Aerospace and Defence Industries Association of Europe,” which “could provide valuable input for the selection of stakeholder representatives.”

The ASD is the main network representing the interests of military giants, or what people in Brussels would more simply call a lobby group. Its members include some of the same defense contractors whose CEOs sat on Bienkowska’s High Level Group, as well as national associations representing their industrial interests. Essentially, industry representatives together with associated experts and politicians suggested that the Commission look to them for help regarding innovations in military policy, from which they would end up being the main beneficiaries.

There’s nothing new about the way the EU is using extraordinary research funds to leverage policy-making for the benefit of the military industry. Thirteen years ago, the Commission followed much the same process in relation to homeland security, when another High Level Group (with a membership almost identical to that of Bienkowska’s) delivered the report “Research for a Secure Europe,” setting in motion an identical process. What began as a marginal pilot research program eventually injected 3.5 billion euros into the EU’s budget for the direct procurement of biometrics, surveillance equipment, and other security goodies. A report commissioned in 2014 by the European Parliament’s liberties watchdog committee, LIBE, severely criticized the high-level fora shaping security and defense policy as a “closed community in the making, interested in the development of huge margins of profits for the industry.” “Funded security research in the future,” it warned, “will be mainly put at the service of industry rather than society.”

But MEP Bodil Valero, Swedish Greens/EFA spokesperson for security and defense, argues that political concerns are even more influential than industry lobbying in promoting the EU’s militarization: “A majority of MEPs and stakeholders here are driven by fear and the willingness to find quick fixes for, in my view, deep structural security problems,” she says. “There are associations which promote using the EU budget for defense purposes and increasing the overall defense expenditures of member states. Nevertheless, it was more the outbreak of the war in Eastern Ukraine and the illegal annexation of Crimea, coupled with terrorist attacks by IS in several European cities, that made this new development possible.”

Videos of meetings of the European Parliament’s Subcommittee on Security and Defense (SEDE) often show a bunch of bored MEPs listening to experts on military and security issues or to geopolitical analysts describing the “Mad Max” world beyond the EU’s borders. But when discussion does take place, it tends to follow the theme of existential threats to the European way of life: Islamist terrorism, Trumpian isolationism, and, especially for MEPs from Eastern European countries, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggressive anti-EU agenda and propaganda warfare. Hard facts seem to be a low priority when estimating the size of the military threat to Europe from the East. The European Institute for Security Studies reported that in 2016 the 28 EU member states invested a massive 206 billion euros on defense. France alone spent 43 billion euros, topping Russia’s figure of 42 billion euros.

The United States has enthusiastically led the push for militarization, putting pressure on its European allies at the 2016 NATO summit to spend 2 percent of their budgets on defense spending—a long-term commitment so far honored mostly in the breach. The German and French defense ministries were quick to respond to the call, submitting their bilateral action plan to the EU on September 11, 2016. Both Merkel and Macron seem keen to cultivate the impression that their push for rapid militarization is a joint agenda. However, the two countries’ military industries compete fiercely for markets, and their political incentives are also in conflict. For Germany, whose defense industry lags behind in relative terms, Europeanization could bypass the mistrust a strictly German military expansion would evoke. For France, the joint initiative is another attempt to tame German hegemony after the failure of the Eurozone to contain it.

The European Parliament has not always been friendly territory for the emerging military-industrial complex. Ben Hayes, a British EU security policy expert and author of path-breaking reports for Statewatch and the Transnational Institute, remembers that the industry and the European Commission faced significant opposition within the European Parliament as they tried to build a European security policy in the decade after 2004. “Criticism from MEPs in the committees was often fierce, and various surveillance super-projects pushed by the Commission, like the Passenger Name Records and Smart Border, took years to get through the negotiation table and get political approval,” he remembers.

The transition from soft securitization to hard-core militarization currently under way is unlikely to take that long. MEPs worried about Russian military ambitions or hybrid security threats like cyber attacks have turned the European Parliament into a much more welcoming forum for such initiatives. For those who have pursued militarization all along, like the ever-present Christian Democrat Michael Gahler, the prospects have never been better. At the end of last year, Gahler urgently reminded his fellow MEPs that “using the momentum on security and defense policies after the Brexit referendum and the election of Mr. Trump in the US is crucial for pushing ahead”—and proposed the revival of Permanent Structure Co-operation (PESCO) a mechanism known among EU officials as “the Sleeping Beauty of the Lisbon Treaty,” which could send EU forces into direct military action.

Around the time Bienkowska’s High Level Group was concluding its duties, two separate reports on EU military policy were also in the pipeline, one initiated by Estonian MEP and ex-foreign affairs minister Urmas Paet and the other prepared by Ioan Mircea Pascu, the Romanian Social Democrat vice president of the European Parliament. Both reproduced the key findings of the Bienkowska group’s report; both were approved by the plenary of the European Parliament, Paet’s on November 22 of last year, Pascu’s on the 23rd. Their extensive proposals included the creation of a new financial instrument to support EU military research, putting in place a platform to help the EU executive coordinate political imperatives and industrial needs, a new European Council of defence ministers—and the development of the EU’s capacity to deploy armed forces in crisis zones.

It did not take long for Juncker to come up with specific plans for the new policy. Actually, it took one week. On November 30, in a not-so-widely noticed press release, he announced the Commission’s European Defence Action Plan (EDAP), which was somewhat more ambitious than that envisaged by all three reports: He was putting serious money on the table. A newly proposed fund, to run from 2020 onward, earmarked 500 million euros a year for research and development and foresaw a parallel funding stream of 5 billion euros a year, essentially for procuring military equipment through groups of member states. The total amount approached 39 billion euros, partly from EU resources and partly from national contributions, which—as an extra incentive to member states to spend more—could be excluded from the EU’s budget-balancing rules. Seven years earlier, at the peak of its debt crisis, Greece had asked for the same flexible approach, only to receive a flat no.

One of the few dissenting voices to this ambitious plan was that of Laetitia Sedou, the program officer of the European Network Against the Arms Trade (ENAAT), a modest umbrella group of European anti-militarization organizations. Before the EU’s 60th birthday party in Rome last March, she wrote to European Council President Donald Tusk, Juncker, and European heads of state, arguing that Europe “should remain a peaceful club of nations instead of contributing to a new arms race.”

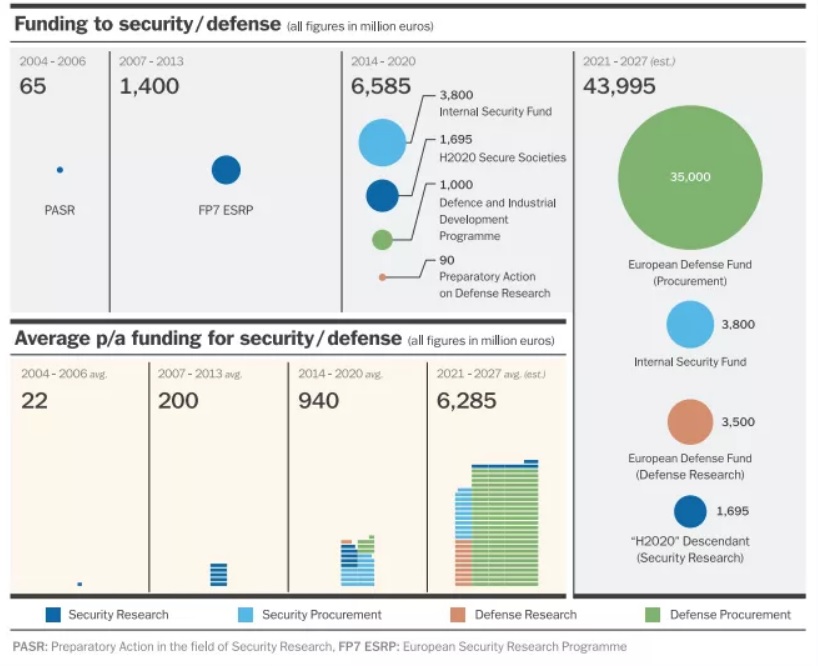

Sedou’s letter describes the wider militarization of all aspects of the EU budget. Besides the billions of euros the EDAP was proposing to syphon directly to the military industry, she wrote, the EU was working toward facilitating the access of arms producers to a range of EU funding opportunities, including structural funds, development aid intended to alleviate poverty, and even Erasmus, the EU program for education and training: “Already in January 2017 a call for proposals launched under Erasmus includes defence as one of six priority areas.” Even without the diversion of subsidies earmarked for peaceful purposes, if Juncker’s budget projections hold, the direct allocation of EU funds to military contractors and their homeland-security subsidiaries will have exploded from zero in 2004 to tens of billions of euros by 2020.

The creation of a military-industrial complex is linked, by Euroskeptics and critical pro-EU interlocutors alike, to the potential creation of an EU army, a dream cherished by various EU politicians. But Sedou sees it more as an attempt to exploit unused industrial capacity. “An EU of defense is a political process,” she says, “while what the EC is proposing is a pure industrial process.”

Juncker himself seems to think otherwise. In March 2015, he told the German Welt am Sonntag newspaper, “A joint EU army would show the world that there would never again be a war between EU countries. Such an army would also help us to form common foreign and security policies and allow Europe to take on responsibility in the world.” A European Commission source has admitted that deployability of EU armed forces is a policy priority. And once the capacity to fund and deploy EU forces has been established, a pretext for sending those forces into the field might not be far behind.

In mid-May, German Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière and his Italian counterpart, Marco Minniti, were already asking for a mission to be set up “as soon as possible” between Libya and Niger to do what EU policy had failed to do in the central Mediterranean: Stop refugees and migrants from getting to Europe. On October 30, EU Foreign Affairs Commissioner Federica Mogherini indicated that joint EU battle groups, each consisting of 1,500 troops, may be deployed in UN missions in Africa. These battle groups could contribute to the new UN mission being demanded by several EU countries to combat the threat of terrorism in the Sahel region and take on smuggling networks there that capitalize on growing insecurity. If so, it would be the first time joint EU military forces have seen action anywhere in the world.

The emergence of a military-industrial complex in conjunction with opportunities for the EU to go to war will inevitably have a profound impact on the future of the EU. In the words of Bodil Valero, “As an MEP from a non-NATO EU member state, I have to say that I do not want the EU to be transformed into a military alliance in charge of territorial defense. This would deeply change the Union’s character.”

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018