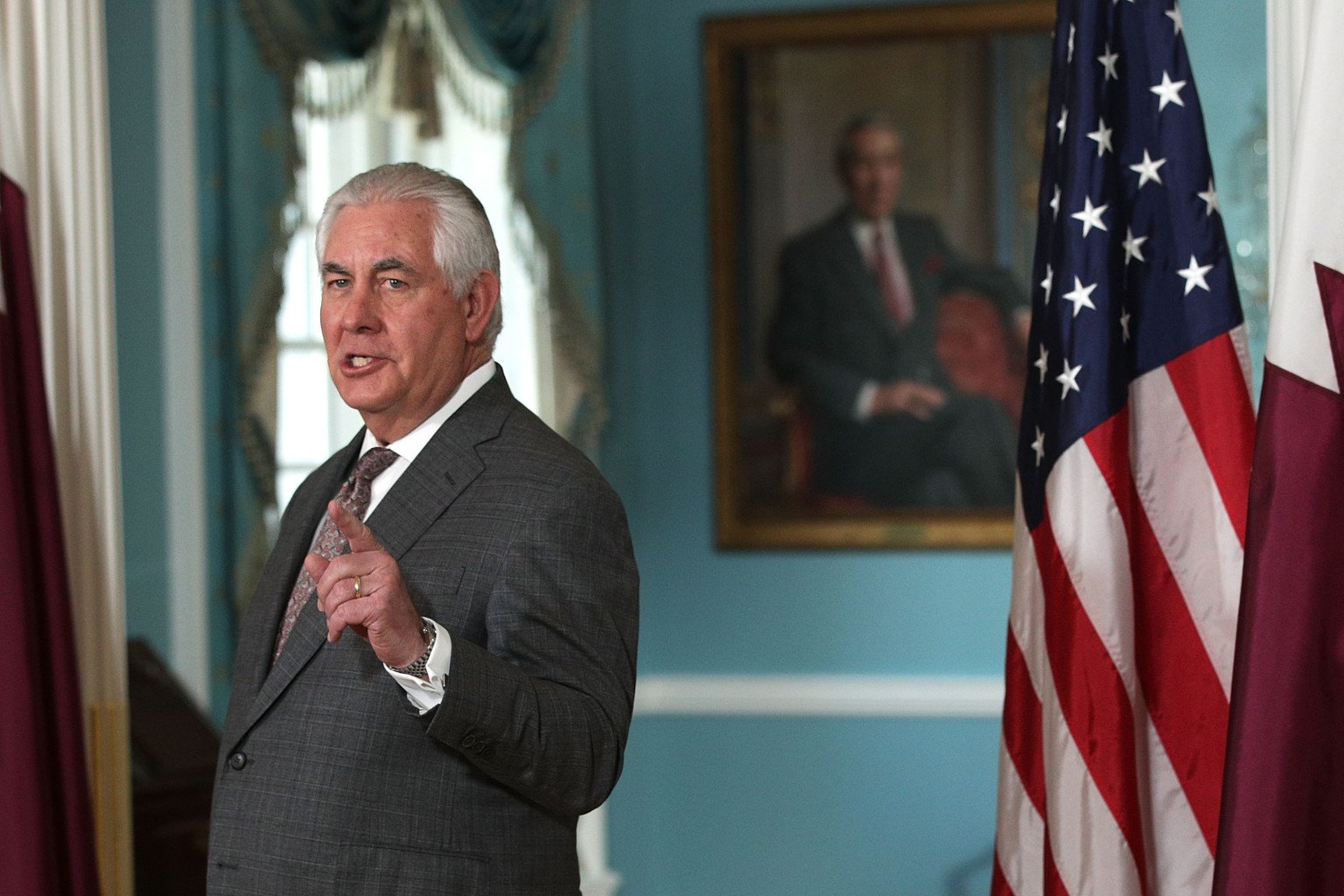

Rex Tillerson Is Underrated

By Stephen M. Walt / Foreign Policy

7 ديسمبر 2017

ver the past year, Rex Tillerson seems to have doggedly pursued the title of Worst Secretary of State Ever. The New York Times editorial board accuses him of “making war on diplomacy,” and contributing writer Jason Zengerle’s recent profile of Tillerson was headlined “Rex Tillerson and the Unraveling of the State Department.” Nik Steinberg published a piece in Politico titled “Rex Tillerson Is Running the State Department Into the Ground” and Michael Fuchs at Just Security asks if the department is “being intentionally gutted.”Washington Post blogger and Fletcher School professor Daniel Drezner has raked Tillerson over the coals repeatedly, referring to him as an “unmitigated disaster” and calling on him to resign. Other critics accuse him of being ineffective, isolated, and clueless about America’s role in the world. (Full disclosure: I’ve been part of this critical chorus too.)

The reasons for these lamentations aren’t hard to discern. Top positions around the department remain unfilled, morale is at rock bottom, and experienced senior diplomats are resigning in droves. Tillerson has yet to offer a clear vision of what U.S. foreign policy ought to be, has made little or no progress on the major diplomatic challenges the United States currently faces, and is sometimes at odds with President Donald Trump himself. He openly supports cutting his own department’s budget and has brought in an outside consulting firm to propose major reforms that have veteran officials up in arms. Given all that, no wonder so many observers find little to praise and much to condemn.

But last week I had an odd thought: Is it possible we’re being unfair to him? I’m not suggesting Tillerson belongs up in the pantheon with James Baker, Dean Acheson, or (more controversially) Henry Kissinger, but could it be that Tillerson is getting a bit of a bum rap?

For one thing, the list of ineffective secretaries of state is a long one, and it’s by no means obvious where Tillerson ranks in that dubious company. Remember William Rogers? Dean Rusk? John Foster Dulles, or Warren Christopher? None of these men covered themselves in glory, and some of them (e.g., Rusk) supported policies that were genuinely disastrous for the United States. Nearly everyone thinks Colin Powell is a nice guy and a genuine patriot, but he failed to halt the neoconservative drive for war in Iraq and will never fully live down the embarrassing, error-ridden “briefing” about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction programs that he gave to the United Nations Security Council in 2003. Tillerson may not be very good at his job, but some of his predecessors were pretty inept too.

Second, Tillerson is serving a president who is genuinely clueless about foreign policy yet seems to think he’s some sort of a strategic genius. Trump is good at selling himself and positively world-class at conning gullible people, but there’s a great deal he simply doesn’t know about foreign affairs, and some of the things he thinks he knows are wrong. He won’t stop tweeting twaddle, and smarter leaders than he is have taken his measure and figured out that flattering his ego and pandering to his business interests will get him to do what they want. Given the president he serves, how effective could Tillerson possibly be?

Third, some of Tillerson’s more controversial actions — such as his efforts to reorganize the State Department — were long overdue. The cruel fact is that the State Department, and especially the foreign service, has been a neglected institution for a long time and has not been adapted to the realities of 21st-century diplomacy. The United States is still the only great power that routinely assigns about a third of its ambassadorial positions to unqualified amateurs, simply to reward them for their campaign contributions. Meanwhile, career foreign service officers rarely get the opportunities for career development that their counterparts in the armed services or in other countries’ diplomatic corps enjoy. That’s not their fault, of course, but its another sign that serious reform is needed.

Moreover, the role that local diplomats play overseas has changed markedly since the 19th or even the early 20th century, given the rapidity of global communications and the vast quantities of information amassed by other agencies, and the growth of other agencies also engaged in different aspects of foreign affairs. These facts are by no means an argument for “gutting” the department, but rethinking its proper role and structure in these radically different circumstances is hardly a crazy notion.

Furthermore, over the years the State Department has acquired a lot of additional tasks and burdens — often at the behest of Congress — in the form of various specialized bureaus or special envoys who are supposed to deal with some particular international issue. So the current State Department organizational chart includes the traditional regional bureaus but also a global AIDS coordinator, an assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights, and labor, an ambassador-at-large for counterterrorism, and literally dozens of other special envoysassigned to particular narrow tasks. Most of those special envoy positions are still unfilled under Trump, but it is not obvious that putting someone in these jobs would make U.S. foreign policy more effective.

Don’t get me wrong here: I have enormous respect for many U.S. diplomats and I think the kind of personal engagement and local intelligence that a smart and experienced ambassador and staff can provide is invaluable. Many of the recent failures of U.S. foreign policy were the result of an inadequate understanding of local political conditions and regional realities, and that is precisely the sort of situational knowledge that experienced diplomats can provide. Skilled diplomats also conduct public and private diplomacy in foreign societies and help explain the U.S. perspective to local populations and elites. In that sense, they are sometimes a very effective sales force and a barrier to anti-Americanism. As I’ve written elsewhere, many of America’s biggest foreign-policy successes were diplomatic triumphs rather than purely economic or military achievements, and having expert diplomats with knowledge, vision, and experience was central to these successes.

So the United States needs a first-class diplomatic capacity, even if a case can be made that the State Department needs re-engineering. That’s what Tillerson says he is trying to do. Some of Foggy Bottom’s current inhabitants weren’t going to like it no matter what he proposed, for the same reasons that university faculties howl in protest whenever a new president wants to shake up the curriculum or tinker with the academic calendar. Again: I’m not saying the reforms Tillerson eventually decides to implement will be the right ones, but the fact that some current employees are unhappy at the prospect of change is entirely predictable.

Finally, let’s not forget that the State Department’s role was declining long before Tillerson showed up. The last secretary of state who had a lot of genuine foreign-policy clout was James Baker, who was both an extremely talented negotiator and also enjoyed an unusually close working relationship with President George H.W. Bush and national security advisor Brent Scowcroft. But that was more than a quarter-century ago. Since then, successive presidents have increasingly marginalized the department and concentrated more and more power in the White House itself, where the National Security Council staff has ballooned. The power of the Pentagon has been growing too, with regional combatant commanders controlling vastly greater resources and wielding a lot more influence than local ambassadors or even the secretary of state. This was true under Bill Clinton, true under George W. Bush (where Vice President Dick Cheney’s office also had considerable power), and true under Barack Obama. Hillary Clinton was a loyal team player and energetic salesperson during Obama’s first term, but she was given little independent authority and had little impact on policy. John Kerry was more influential — especially on the Iran nuclear deal — but that was mostly because Obama was happy to let him handle impossible tasks like Israeli-Palestinian peace and willing to let him take the fall if these initiatives failed.

Even if he were some magical combination of Bismarck, Metternich, and George Marshall, in short, he might find it hard to run a successful foreign policy these days.

Have I persuaded you that Tillerson’s critics are being unfair to him? Probably not. And to be fair, there is an obvious reason why the limited defense I’ve been laboring to construct is not that persuasive: Neither Trump nor Tillerson has ever given any indication that either of them understands the importance of a strong State Department or the value of diplomacy itself. It would be one thing if either man had ever presented a clear and compelling vision of what U.S. interests are and how they intended to achieve them, beyond bumper-sticker slogans like “America First.” If either of them had done so, and then explained how a reformed and much-improved State Department fit into their plans, we’d have some reason to give them the benefit of the doubt or at least credit them for trying to make things better.

But a genuine commitment to diplomacy — what former Ambassador Chas W. Freeman calls the technique wherein a nation “advances interests and resolves problems with foreigners with minimal violence” — has been conspicuously lacking in the Trump administration. Instead of building broad international support for policies that would advance U.S. interests in key regions or on important issues, Trump seems to delight in telling foreign leaders that he’s only looking out for himself and doesn’t care who knows it. Meanwhile, he wants to inflate an already bloated military budget, bomb more countries, and dismantle existing agreements even when they are working, and he thinks skilled subordinates with deep and genuine expertise aren’t important because he’s “the only one that matters.”

All of which leads me to feel a certain sympathy for poor Secretary Tillerson. He’s clearly smart, has few illusionsabout his volatile boss, and seems to be stuck in an unwinnable position, where the best he can hope to do is minimize damage. The real question, therefore, is not whether Tillerson is the worst secretary of state ever. The real question is: Why hasn’t he already resigned on principle and gone home to enjoy a pleasant and wealthy retirement?

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018