A Memoir of Life as Che Guevara’s Kid Brother

By Peter Canby/ New Yorker

13 أكتوبر 2017

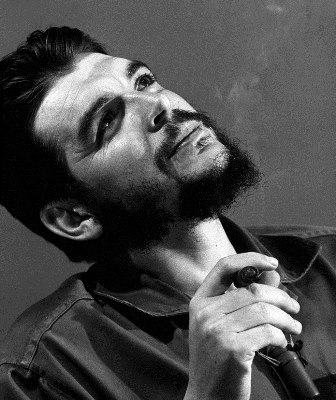

n October 9, 1967, just over fifty years ago, the Argentine revolutionary Ernesto (Che) Guevara was shot to death by a Bolivian Army sergeant in a schoolroom in a tiny hamlet in southeastern Bolivia. The Bolivians had hunted him down with the assistance of the C.I.A., which hoped to bring an early end to his role as a symbol of the struggle against the ravages of capitalism. But, after the execution, Che’s body was flown to Vallegrande, the nearest air base, sixty kilometres away, where it was put on display in the laundry room of a local hospital, and almost immediately the corpse began to take on a life of its own. In his biography of Che, my colleague Jon Lee Anderson writes that nuns working at the hospital swore that the open eyes of Che’s cadaver followed them around the room. Local peasants, who as a group had been reluctant to support Che’s insurgency, began to snip off locks of his hair to use as talismans; gradually, he was transformed into San Ernesto de La Higuera, a santo with special powers to assist the poor. When photographs of Che’s carefully laid-out corpse began to circulate more widely, the art critic John Berger pointed out the striking similarity between Che’s body and the body of Jesus as portrayed by the Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna in “Lamentation of Christ.”

One person who doesn’t believe in what he refers to as these “idiotic stories” is Che’s youngest brother, Juan Martin Guevara. In his recently published book, “Che, My Brother,” (written with the French journalist Armelle Vincent), Juan Martin observes that all these anecdotes “tend towards the same goal: to turn Che into a myth.” Since Che’s death, the Guevara family has, for the most part, avoided speaking publicly, and Juan Martin’s professed intention, in breaking his silence, is both to counteract the degree to which Che’s image has been co-opted (in 2012, for example, Mercedes-Benz designed an advertising campaign that replaced the star on Che’s beret with the Mercedes logo) and also to explicate Che’s ideas as “a thinker and a social innovator.” “I share his ideas,” Juan Martin writes. “I am a Marxist-Leninist, a Guevarist.” In actuality, though, “Che, My Brother” is light on ideology and, instead, succeeds remarkably well as a personal and family memoir, benefitted by the authority of a writer who indisputably knows his subject well.

While biographers have described Che’s family as coming from the Argentine aristocracy, Juan Martin observes wryly that this formulation “always makes me smile. The oligarchy has two components: power and money. My parents had neither.” Che and Juan Martin’s father, Ernesto Guevara Lynch, was the charming but feckless son of a “good family,” with no degree and a life-long tendency to involve himself in failing enterprises. Juan Martin describes his father in his youth as a “seasoned seducer” who, “at nightfall, headed off, carrying a weapon, to dance tango in the disreputable suburbs of Barracas, a neighborhood on the outskirts of Buenos Aires.” At the time, Juan Martin writes, Argentina’s national dance was the “exclusive domain of the working classes and immigrants.” “Decent folk” of the sort his father and mother came from “believed that this erotic pas de deux, which mimicked the motions of love so closely, was completely depraved.” When Ernesto met Che’s mother, Celia de la Serna y Llosa, she was the impressionable daughter of an old and wealthy family and was just emerging from the Convent of the Sacred Heart. During her schooling, she had considered taking the veil, but, after the nuns forced her to recite the Lord’s Prayer “10,000 times over” and mortify herself by putting ground glass in her shoes and kneeling on corn kernels, she decided that she no longer believed in God. Celia and Ernesto dated for only a few months before marrying. Her family boycotted the wedding.

After marrying, the young couple made a whimsical attempt to carve a yerba-maté plantation out of the jungle—on a “narrow stretch of lava and mud hemmed in between Brazil and Paraguay,” Juan Martin writes. Ernesto started by building a chalet on stilts, overlooking the Parana River. By the time the plantation failed, Celia had given birth to Che, the first of the couple’s five children (Juan Martin is the youngest). The infant Che suffered from severe asthma, and so the Guevaras chose to move to a more salubrious climate. They eventually arrived, very short on cash, in the mountainous province of Córdoba. There they settled in the spa town of Alta Gracia, where Ernesto took occasional jobs renovating hotels. The Guevara family moved regularly within Alta Gracia and, as Juan Martin puts it, each house they inhabited was invariably “transformed into a shambles.”

In this way and others, the Guevaras had a distinctive style. Unlike other residents of Alta Gracia, they supported the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War and didn’t go to church. Celia scandalized the neighbors by cutting her hair short, wearing trousers, and driving a car. The Guevara kids came and went as they pleased and hung around with “proletarians and peasants”—anyone they liked. The family collected books, which they lent freely to friends. Juan Martin described it as a “hyper-politicized atheist environment.”

Che was perhaps the wildest member of the family. He was always handsome—with “large expressive, laughing eyes, a thick black mop of hair, and an easy smile,” Juan Martin writes—but he was indifferent to his appearance, wearing “the same shirt of threadbare nylon, hanging half out of his trousers, with mismatched shoes picked up in a jumble sale.” Che was the oldest, but, Juan Martin writes, “he didn’t play the role of the bossy and overbearing big brother; instead, he was protective. For him, knowledge and learning were essential and, like my parents, he never tried to impose things.”

From an early age, Che developed a strong sense of social justice.The Guevaras moved back to Buenos Aires, in the early nineteen-fifties, by which time Ernesto and Celia had split, and the family employed a Bolivian maid, Sabina, a Quechua-speaking Aymara Indian from the highlands who spoke little Spanish. She and Che became very close, and despite the maid’s lack of Spanish, the two spent hours talking. Che was curious about her life, her origins, and her people. At this point, Che was in medical school. As soon as he graduated, he took off on his famous motorcycle ride to explore South and Central America. His first objective was to visit the Bolivian highlands, where he hoped to become familiar with the hardships experienced by the Aymara people.

Che’s trip up the spine of South America—to a Peruvian leper colony, to Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala (where he experienced the 1954 U.S.-supported right-wing coup), and Mexico (where he met Fidel Castro)—is a trip from which, from his family’s point of view, he never returned. During the six years of his wanderings, his communication was erratic and depended, in part, on when he could afford a postage stamp. His parents and siblings worried about him, feared he might be killed, and missed him terribly. “Whether he wrote to us personally or not, the result was the same,” Juan Martin writes. “Each letter was an event around which the whole family gathered. Everyone’s efforts were required: his handwriting was illegible and sometimes took hours to decipher.”

Meeting Fidel, of course, got Che involved in the Cuban Revolution. The Guevara family viewed Cuba as a kind of quaint, distant Illyria, and their son’s involvement there was an inexplicable curiosity. But, as the struggle in the Sierra Maestra grew in intensity, the infrequent communication from Che made them take the conflict more seriously, and it became a source of intense anxiety. In early January of 1959, only a few days after the Cuban rebels succeeded in ousting President Fulgencio Batista from power, the phone rang at the Guevara house and Celia answered. “Hola vieja. It’s your son Ernestito,” Che said. Two days later, Castro flew the Guevara family to Cuba, to celebrate the success of the revolution. They were received there with open arms—“I was strutting about in the three-piece suit my parents had bought me for the occasion,” Juan Martin writes—and Celia Guevara, especially, became immensely proud.

Although Che never fell out with Castro, within a few years, the two men’s plans diverged. Castro began to bring Cuba—for its economic survival—closer to the Soviet Union, a country which Che had grown increasingly critical of. Che’s interest was less in nation-building than it was in universalizing the process of liberation of the Third World poor. Initially, Che attempted to begin an insurgency in the Congo. When that failed, he tried again in Bolivia, no doubt influenced by his long-ago relationship with Sabina. For the Guevara family, the last few years of Che’s life were shrouded in mystery. In 1965, Celia was diagnosed with cancer, but didn’t want to burden Che with the news. She wrote to him that she wanted to return to Cuba to visit as soon as possible. Che put her off, telling her that he was going off to cut sugar cane for a month. In fact, he was, as Juan Martin puts it, “training for combat and planning the next stage of his life.” Che and Celia never saw each other again. She died a few weeks later, two years before Che’s own death.

Juan Martin was reporting to his job as a dairy-truck driver in Buenos Aires when he learned of his brother’s execution. He arrived at work before dawn and, he writes, “There it was, the headline of the daily Clarín,” announcing Che’s death in Bolivia.” The famous photograph of Che’s body stretched out in the Vallegrande hospital laundry room was on page two. Che’s death had been mistakenly announced multiple times in the papers before, and the family was divided on whether the story this time was real. The Guevara’s second son, Roberto, flew to Bolivia to investigate but was given the runaround. The story was finally confirmed by Fidel, to whom a Bolivian soldier had mailed Che’s diary and his amputated hands, to show his fingerprints. Che had been especially close to his two sisters, Celia and Ana Maria (both of whom were architects), and his death was devastating for them. Speaking for all the family, Juan Martin writes, “The pain was intense. It went on for ever.”

Juan Martin was twenty-three years old when his brother was killed. He could not bring himself to visit the site of Che’s death until almost fifty years later. His account of that pilgrimage, included in the opening of his book, offers a poignant view of the burdens that come with having a family member who has become a legend. In Bolivia, Juan Martin’s tour guide was shocked to discover who he was. A Japanese tourist accosted him and burst into tears. “Being the brother of Che has never been a trivial matter,” he writes. “When people learn who I am, they’re dumbstruck. Christ can’t have any brothers or sisters. And Che is a bit like Christ.”

The Cuban Revolution had consequences in Argentina. For years, the country’s politics had been dominated by the populist strongman Juan Perón—whether he was in or out of power. But the Cold War raised the stakes. When Perón, died, in 1974, right-wing Perónists and the military began a violent repression of the left. Juan Martin, who had been running a bookstore called “La Pulga” (“The Flea”) in Buenos Aires, did not publicize his connection to Che, but he also worked for the Partido Revolucionario de los Trabajadores, a left-wing Perónist “politico-syndicalist organization.” He was arrested for his political activities in 1974, then released, then arrested again the following year, along with his wife, Viviana Beguán. The two were imprisoned separately for more than eight years. In one sense, they were lucky: by being arrested when they were, they gained legal identities within the prison system, and thus narrowly avoided the worst of the “dirty war,” in which tens of thousands of compatriots were either “disappeared” or simply assassinated on the street. (As it was, Viviana’s parents, who were not political, were picked up, tortured and, while their daughter and son-in law were in prison, thrown out of an airplane into the Rio de la Plata.) One of Juan Martin’s memorable visits in prison was from an Argentine counter-insurgency officer who had learned that he was Che’s younger brother. “What an incredible guy, that fantastic brother of yours…. What a pity [he] chose the wrong side!”

The Cuban government remained supportive of the Guevara family, and during the Argentine violence most members of the family fled to Cuba. Juan Martin, who chose to stay in Argentina, remains close to Cuba to this day, and to his many nieces and nephews, including to Che’s five children and several of his own children, who live there. At one point, Juan Martin briefly enjoyed success as the biggest importer of Cuban cigars into Argentina; but, when his plans for a Cuban-themed restaurant failed, he lost what small fortune he had accumulated.

Juan Martin is not blind to the shortcomings of the Cuban government or even of his brother, who, after the revolution, organized the regime’s firing squads. At one time, Juan Martin intercepted a shipment of cigars that he believed included cocaine. He reported it to the Cuban authorities, but no action was taken. He nevertheless remains deeply supportive of the Cuban Revolution and wonders why, when people point out Cuba’s shortcomings, they compare it unfavorably to Switzerland or France. “Why not compare it instead to its neighbors, Haiti, or the Dominican Republic, or Honduras? Which of these nations is doing the best? Which gives its citizens health care and an education for free? Which has less crime?”

Juan Martin points out that his brother—although a great reader of Marx—was most interested in finding ways to construct a society “based not on profit but on humanitarian principles and an ideal of honour, solidarity and fraternity.” Perhaps this idealism was fated to clash with the hard realities of the world around him, but, Juan Martin, loyal younger brother that he is, feels that the world still desperately needs a discussion of the ideals he attributes to Che. He writes of staying in touch with two friends of his brother, veterans and survivors of the Bolivian campaign, who told him that Che spoke often of all his siblings, but regarded Juan Martin as his spiritual heir—the one who could continue his fight and bring it to a successful conclusion. He adds, “That’s what I think of today, while writing this book.”

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018