Dim prospects for Lebanon’s economy

Rami Rayess / The Arab Weekly

5 يونيو 2017

Lebanon has never enjoyed a strong economy and the current tranche of political manoeuvring looks unlikely to mark any serious reversal of decades of neglect and political infighting.

Lebanon’s economy has never really lived up to its reputation for vibrancy. Even in the supposedly halcyon days of the 1960s and ‘70s, there were significant concerns the economy was too reliant on tourism and commercial services rather than developing and strengthening other sectors, specifically industry and agriculture that might provide a long-term base for the future economy.

What economic development was undertaken was haphazard and distributed unevenly, producing little but high poverty levels and the concentration of power and wealth within established elites.

The destruction wrought by the years of civil strife from 1975-90 also left its mark on the economy. The staggering costs of reconstruction and the corruption that have followed pushed public debt to the point where it now eclipses GDP by 140% — the third highest internationally after Japan and Greece.

Following the election of a president last October and the subsequent appointment of a new cabinet, hopes were high that the economy would be given priority. However, the seemingly rushed approvals granted to the long-awaited oil and gas decrees have only served to increases public fears of increased corruption and a further deterioration in economic transparency. Subsequent government deals relating to the provision of electricity and telecoms have reinforced those fears.

Beyond the country’s historic and largely self-inflicted woes, are pressures affecting the fragile Lebanese economy: The influx of Syrian refugees, estimated at more than 1.5 million; the American sanctions whose targets seem to fall wider than simply Hezbollah and its institutions; the negative effect of the long-term political and constitutional turmoil the country has endured and the high unemployment and the low development rates that exist across Lebanon.

It’s also worth remembering the 400,000 or so Palestinian refugees who have been resident in, and dependent upon, Lebanon since 1948.

Given the severity of those challenges, plus the chaos that has come to characterise the electoral law reforms, expectations that serious economic reform may be under way soon are low.

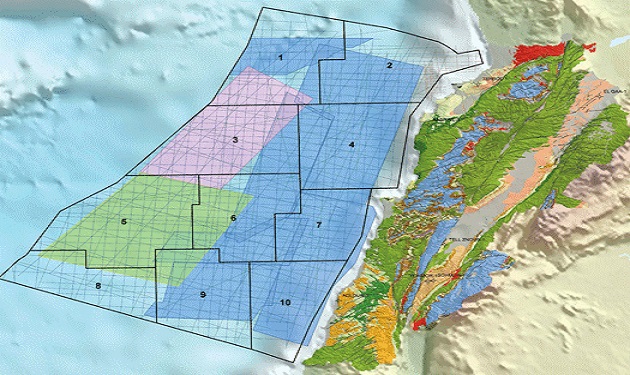

However, the government estimates that 96 trillion cubic metres of gas and 865 million barrels of oil lie beneath unexplored areas off the country’s coast. After being stalled since 2013, exploration rights for those fields are open for tender and, if successful, promise returns of more than three times the country’s national debt.

Despite the IMF’s apparent approval of the process, delays in establishing the Lebanese National Oil Company have increased public scepticism over the government’s ability and willingness to carry out continued reform with the transparency many have hoped for. Moreover, delays in the creation of the sovereign fund have heightened concerns over possible corruption.

The international financial support that Lebanon called for has fallen far short of what is required and many promises by potential donors have not been kept. True, there is increased awareness from the part of the international community of the enormous pressure the Syrian refugees exert on the Lebanese economy, particularly as many are expecting a prolonged stay in the country.

However you look at it, the prospects for the Lebanese economy are dim. Political factions have unanimously failed to construct a common approach for resolving economic issues separately from their political differences.

Ultimately, all will face the final verdict of the electorate at the ballot box.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018