The Passions of Medieval Jerusalm

Peter Schjeldahl / New Yorker

1 أكتوبر 2016

At the Met, a captivating show displays the visual evidence of a time and place roiled by dozens of ethnic and religious constituencies.

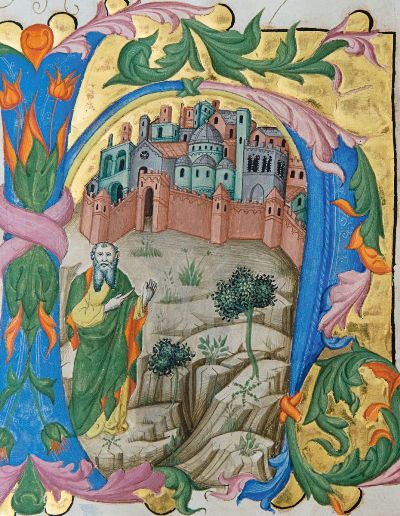

usalem, 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven,” at the Metropolitan Museum, is a captivating show of some two hundred objects from the era of the Crusades. There are manuscripts, maps, paintings, sculptures, architectural fragments, reliquaries, ceramics, glass, fabrics, astrolabes, jewelry, weapons, and, especially, books—in nine alphabets and twelve languages. The works, from sixty lenders in more than a dozen countries, express the Jewish, Islamic, and Christian cultures of the time, the three great Abrahamic faiths sharing a city holy to them all, when they weren’t bloodily contesting it. The installation is lovely: rooms in gray and blue are filled with a cumulative haze of spotlights, designed not for drama but for ease of attention; the show, though immense, won’t exhaust you. There are mural-like video projections of the city today and brief video interviews with representative citizens. The ambience is conducive less to learning than to dreaming. This feels right for a history that is incomprehensible without reference to religious passions. I am reminded of Marianne Moore’s description of poems as “imaginary gardens with real toads in them.” Jerusalem was then, as it remains for many, as much an idea as a locale. In 2000, the British Journal of Psychiatry reported on about twelve hundred cases, during the previous decade, of “Jerusalem syndrome,” in which ordinary tourists were seized by convictions of a sacred mission and made public nuisances of themselves, often by sermonizing at holy sites while clad in hotel sheets.

In the introduction to the show’s catalogue, the curators, Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb, tell of meeting with Theophilus, the Greek Orthodox patriarch of Jerusalem. He asked them, “Whose story do you intend to tell?” They answered that they hoped “to tell everyone’s story, and no one’s.” And so they have, to the extent possible, with visual evidence from a time and a place roiled by dozens of ethnic and religious constituencies. Most of the objects were not made in Jerusalem, and only a quarter of them are from collections there. But their association with the city isn’t strained; they evince a gravitational tug that was felt, according to Boehm and Holcomb, by people in regions as far-flung as Iceland and India. The show documents the medieval city’s allure in sections entitled “The Air of Holiness” and “The Promise of Eternity,” and follows its consequences in “The Pulse of Trade and Tourism”—involving waves of pilgrims and the commerce that served them—and “The Drumbeat of Holy War.” Regarding the last section, we are led to reflect on the era’s amplification of the concepts of Christian bellum sacrum—“God wills it!” was the Crusader battle cry—and Islamic military jihad, waged “to uproot the unbelievers,” as a Muslim leader declared in the twelfth century.

Jerusalem was among the first conquests of the Arab Caliphate, in 638. It was a polyglot city, in which Christians suffered oppression, when, in 1099, armies of the First Crusade took it and massacred nearly all the Muslim and Jewish inhabitants. The lavishly renovated Church of the Holy Sepulchre, on the supposed site of Christ’s Crucifixion and Resurrection, stood near the Al Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, built on the ruins of the Hebrew Second Temple, which were temporarily converted to a palace and a church, respectively. (The rock enshrined is thought to be the one on which Abraham was to have sacrificed Isaac, and from which, in 621, Muhammad ascended to Heaven during his night journey.) Muslims led by Saladin, the first Sultan of Egypt and Syria, retook the city in 1187, and several subsequent Crusades failed to achieve more than fleeting footholds there. But a regime of general tolerance, instituted by Saladin and continued by Mamluk sultans, prevailed throughout most of the following two centuries, drawing visitors including the Spanish poet Judah al-Harizi, who characterized his days in Jerusalem, in the early thirteenth century, as “carved from rubies, cut from the trees of life, or stolen from the stars of heaven. And each day we would walk about on its graves and its monuments to weep over Sion.”

As a cultural center, the city was more a destination than a fount of creativity. Medieval invention from all points of the compass generated echoes in the area, with such hybrid effects as Christian symbolism engraved on a dagger-scabbard in a fabulously intricate Arab style. The effigy on the tomb of a Crusader knight—French, from the thirteenth century—finds him armed with a Chinese sword. (How he got it, by purchase or in combat, is among the time’s innumerable untold tales.) The show’s wealth of calligraphic books includes translations between languages and faiths. Even a non-bibliophile like me cannot help being riveted by the beauties and the significance of the tomes on display. Equally striking is the historical drama of such documents as a letter from the Spanish philosopher and scholar Maimonides, in 1170, seeking funds to ransom Jewish hostages held in the Holy Land.

The aesthetic appeal of the exhibits is continual and intense, but concentration on it can feel disrespectfully indulgent. Message, not medium, is the motive of even the most decorative work, in which visual pleasure serves to enhance belief and, perhaps, to give a foretaste of Paradise. Partly, this is true of all properly regarded medieval art and design, from the time before Giotto and Duccio began insinuating personal style into painting. Most of the work in the show is not credited to a named artist. An exception is Sargis Pidzak, an Armenian who made superb illuminations for a Gospel book dated 1346. Another illustration, in a beautiful Italian Torah, of sacrificial rites in the courtyard of the Temple, is attributed to the place-holding “Master of the Barbo Missal.”

The assumptions of the pre-Renaissance world are irremediably alien to most of us. But this show, more than any other that I can immediately recall, closes mental circuitry between then and now, owing to an exquisitely managed sense of collective drives and emotions that have not ceased to influence human affairs. The first of two ravishing stained-glass roundels—the only ones surviving of fourteen Crusade windows from the twelfth-century Church of St. Denis, north of Paris—shows mounted knights on the march to Jerusalem. In the second, three of them receive crowns of martyrdom from the hand of God. The missing middle of the story is evoked by an undated, probably Egyptian, watercolor of a battle that abounds in severed heads and legs. The rumble of violence renders sharply poignant the show’s more prevalent invocations of piety and peace.

In the uneasy peace of today, there are tensions even within communities of faith. In one of the video interviews, an amusing Armenian Orthodox priest, Father Samuel Aghoyan, says that at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which his congregation shares with Catholic and Greek Orthodox ones, he must watch that the services of those sects do not run over their allotted time, because the extra length may set a precedent and “become tradition.” (“Sometimes we argue with each other, like members of a family,” he says, in a tone not suggesting mild demurrals.) More astringently, the writer Ruby Namdar testifies to the “wound that, deep inside, never healed,” for Jews, of the lost Temple. The merchant Bilal Abu Khalaf displays the fabrics and liturgical garments that he sells to groups from all three religions—an ecumenical business that he maintains, it seems, with an edge of nervous defiance. “I hope in the future to be much better,” he says of the city. Similarly wistful, and gently remonstrating, is the Franciscan friar Father Eugenio Mario Alliata, who says, “You know, Jerusalem, it is called the Holy City, but it is really made Holy City only if we are a little bit holy in it.”

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018