#YouStink: Anatomy of a failed revolution

Makram Rabah / Now

26 أغسطس 2015

It is rather a common occurrence to listen to the Lebanese criticize and condemn their country’s less favorable conditions, ranging from corruption and lack of essential services (water and power) to the more recent garbage epidemic. One could even say that this chronic Lebanese practice of blaming the government has become part and parcel of the Lebanese DNA, as this nation has become renowned for its apathy and indifference.

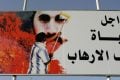

Recently, however, this reputation was challenged by a group of Lebanese who decided to act under the slogan #YouStink to protest against the abysmal failure of the state to address the endemic issue of waste management.

Seemingly spearheaded by activists from the various civil society groups and NGOs, this movement brought together a hodgepodge of individuals ranging from veteran activists, local singers, estranged individuals, aspiring politicians, disgruntled citizens and, strangely, even contractors who were bidding for the next waste management contracts.

While initially this movement meant to merely protest against the garbage issue, people started to steadily swell its ranks, each with their own expectations of perhaps instigating real change by toppling the current government and conducting early elections. These dreams of a bottom-up revolution, at least from the rhetoric of these activists, seemed to be an attainable goal.

Over the weekend, the events that transpired from the rally called for by #YouStink proved otherwise. People who streamed into downtown Beirut to demonstrate against an incompetent government saw their peaceful revolution hijacked both by a clear lack of vision as well as by corrupt hooligans who were sent by parties opposed Prime Minister Tammam Salam.

While the true nature and goals of these vandals was obvious to participants and observers alike, the real damage to this movement came from within.

Initially, #YouStink was mobilized around the issue of waste management and the demand of ordinary, non-partisan citizens that this wrong be corrected. However, gradually this invitation for protest started attracting people with different demands and priorities.

Many of the participants who had the chance to speak on television were invited to the table, but each had a different idea of what would be served. Some of them wanted water and electricity; others wanted better education and healthcare. But, more drastically, there were calls for the immediate resignation of the government.

This latter demand was to become the main driving force of the movement, which unrealistically wanted to tumble the last somewhat-functioning state institution after the office of the president fell vacant more than a year ago. By doing so, #YouStink’s cardinal sin was to demand the impossible from a government already caught in a political whirlpool which has rendered it paralyzed.

Furthermore, the overarching spirit of this movement is somewhat similar to the Paris 1968 youth revolt, which wanted change but never had a clear post-revolution vision. What was left was a group of radicals who refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the state and thus fell outside the framework of legal political action. While the proponents of #YouStink are far from reaching this point, signs indicate a trend toward this bleak outcome.

Additionally, the organizers of this revolution believe that they speak on behalf of the silent majority and thus have a moral obligation to lead the masses into an open confrontation with the state. Many of the people who took to the soap boxes and TV channels kept repeating the word “we,” stressing that they were the vanguard of change. And some if not all of these voices also demanded that everyone join their movement, branding people who refrained from doing so as cowards or collaborators.

These people ignored the fact that a social movement such as theirs is empowered by individuals rather than groups, and to trying to turn these individuals into a new tribe to thrown in with the other 18 Lebanese tribes (sects) is rather an unwise idea.

People demanding change and democracy need to acknowledge that people who refrain from joining their ranks might perhaps have a different take on the matter, or that they might even support the current cabinet — rather uncouth to some but still legitimate and democratic.

Challenging an unfit and defunct system of rule should be the duty of any citizen aspiring to making their country a better place for themselves and their children. But given previous attempts to change and reform the Lebanese system, we should know by now that calling for a revolution and going about it without a clear framework and objective and a single-item demand will only lead to failure.

More importantly, the ruling junta has been using popular rhetoric to mobilize and condition the masses, and over time they have perfected this method. It is vital that anyone wishing to challenge this authority or join this revolution not fall into this populist trap, which will only lead to the fortification of the self-same system they hope to change.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018