Russia and Chechnya: The warlord and the spook

The Economist

12 مارس 2015

Russia’s wars in Chechnya, which the Kremlin says are over, have shaped the country that Russians and the world are now living with

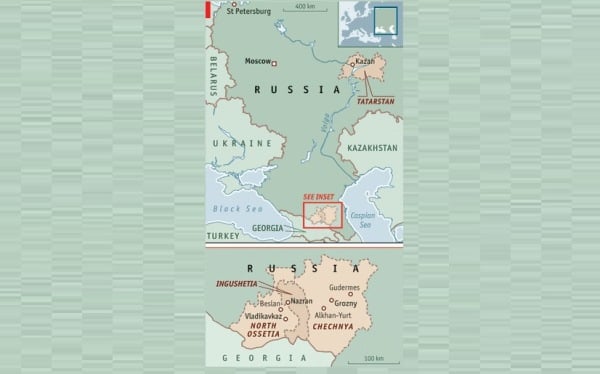

LIKE a high-end bar mitzvah, only with more weapons, the inauguration of Ramzan Kadyrov was held in a giant white marquee, in the grounds of one of his palaces, near the Chechen city of Gudermes. The guests—Russian officers who were once his enemies, rival warlords squirming in dress uniforms, muftis in lambskin hats—brought sycophantic portraits, cars and other gifts fit for a Caucasian potentate. As his pet lions gnawed on their bones outside, Chechnya’s new president made a speech, as short and nervous as a schoolboy’s, in which he vowed to continue the reconstruction of his wretched semi-autonomous Russian republic.

Everyone applauded—and everyone knew the ceremony was irrelevant. Mr Kadyrov has in effect ruled Chechnya since his father Akhmad, also its president, was blown up in 2004. His authority is based on violence, and the backing of Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president. Mr Putin levered Ramzan into his father’s post soon after he reached 30, the minimum age for the job.

Superficially, Mr Kadyrov deserves it. Apartment blocks are adorned with cultish posters of Ramzan: with his father; riding a horse; being awarded his Hero of Russia medal by Mr Putin. Behind the posters, many buildings are still pockmarked or gaping with shell holes. But many others have been rebuilt on Mr Kadyrov’s watch. “He helps everyone,” says a woman in Grozny, just returned from exile to a refurbished building near Minutka Square, once the site of savage fighting. Another Grozny resident says gratefully that Mr Kadyrov’s men repaired all the battle-smashed windows in his neighbourhood.

So the Kremlin has some evidence for its assertion that the two wars fought to quell Chechen separatism—the first rashly launched by Boris Yeltsin in 1994, the second beginning in 1999—are now over. Chechnya is still part of Russia, and any other would-be secessionists have seen the bloody price the Chechens have paid: perhaps 100,000 civilians dead, and many more displaced.

But what kind of Russia is it part of? War with Russia has deformed Chechnya. But perhaps more than anything else in Russia’s post-Soviet history, the forgotten Chechen wars have shaped the angry and authoritarian country Russia has become.

Mr Putin made Mr Kadyrov president; but Chechnya helped to make Mr Putin himself president of Russia. Were it not for the air of emergency engendered by the second Chechen war, which began when Mr Putin was prime minister, the lightening rise of this obscure ex-KGB officer would have met more resistance. The war, and the string of mysterious apartment bombings that preceded it, brought the FSB (the renamed security service that Mr Putin briefly led) back to the centre of Russian politics. And it has been the cause, or the pretext, for many of the hard-line policies of the Putin presidency.

Russia’s gathering suspicion towards the West can be traced in part to the autumn of 2004, and Beslan. It was in that town that terrorists demanding Russia withdraw from Chechnya, and a botched rescue attempt, killed over 330 people, most of them children. Mr Putin used the catastrophe as an excuse to change parliamentary rules and scrap elections for regional governors (who are now all, like Mr Kadyrov, appointed by the Kremlin). And he lashed out at foreign powers which, he said, were scheming to weaken Russia.

Whether or not he really believed that knee-jerk explanation, the aftermath of Beslan embittered Mr Putin’s relations with the United States and Europe (along with the “orange revolution” in Ukraine soon afterwards, which the Kremlin saw as a Western-backed coup). He had sought to portray Chechnya as another front in the “war on terror”, and was outraged when Western diplomats questioned his post-Beslan political reforms and Russian policy in the north Caucasus. He became ever more concerned to counteract American power; Chechnya also helped to determine one of his methods, namely Russia’s renewed courtship of its Soviet-era Arab allies. Dabbling in the Middle East—fraternising with Hamas, prevaricating on Iran—offers a chance to assuage Muslim anger over Chechnya, at the same time as frustrating the Americans.

And the Chechen tragedy helps to explain why Mr Putin’s neurotic bluster plays so well among ordinary Russians. Their country may not be a proper democracy, but the Kremlin is still nervously responsive to shifts in the national mood. Partly because of Chechnya, that mood has become increasingly xenophobic.

Perhaps out of an old solidarity, says one Chechen who has lived in St Petersburg and Moscow, Russians were sympathetic to Chechnya’s plight during the first war. Few are today, especially since the conflict leapt up to Moscow itself, via multiple terrorist bombings and the theatre siege of 2002, in which 130 hostages died. Alexei Levinson, a sociologist, charitably sees today’s antagonism towards Chechens as a displaced form of guilt. Inside, he speculates, Russians know the Chechens have long been wronged, from tsarist colonisation, through Stalin’s deportation of the entire Chechen nation in 1944, to the atrocities that untrammelled media coverage of the first war conveyed to the nation. Whatever its cause, the fear and suspicion are fierce, and have fed a widening loathing of foreigners.

No limits

But even as it elevated Russia’s spooks, and puffed up their paranoia, Chechnya demonstrated and contributed to the chronic weakening of another once-mighty institution, the army. Before the first war started, Yeltsin’s defence minister boasted that Grozny would be taken in two hours. Two years later, with the army exposed as woefully trained and equipped, it ended in humiliating defeat.

When the second one began—now with the Kadyrovs switching sides to fight alongside the Russians—the brutal tactics were more effective. The atrocities were less well publicised, especially after the forcible takeover of NTV, Russia’s last independent national television station. Chechnya was thus a factor in the first big skirmish of another of Mr Putin’s campaigns, against media freedom. Today, real information about life (and death) in Chechnya comes from human-rights groups and a few brave journalists, of whom there are fewer still after last year’s (unsolved) murder of Anna Politkovskaya.

Chechnya, as Russian soldiers put it, became a place “without limits”. Extra pay for combat (real or invented), and the kickbacks required to claim it, were only the most mundane form of graft. There was also kidnapping, the sale of stolen weapons to the enemy and enough oil to kill for. The benighted Chechens were not the only victims of the amorality. Some Russian officers were alleged to have sold their own conscripts to the rebels. Wild abuse of power became normal. Sergei, from Siberia, was shot in the back by a drunken officer in Chechnya in 2003—because, he says, of a row over a woman. Sergei, who now walks with a cane, says serving in Chechnya was like “sticking my head in a refuse pit”.

This depravity and callousness—each year, more Russian soldiers die outside combat than Americans die in Iraq—has helped to generate wholesale dodging of Russia’s biannual draft. (Conscripts are no longer supposed to go to Chechnya, but many still do, says Valentina Melnikova, of the Union of Soldiers’ Mothers.) Families who can afford to save their sons from service do so by paying corrupt recruitment officers and doctors. One result, as a top air-force officer recently complained, is that those who are drafted are often already sick, malnourished or addicted. Another is the exacerbation of social tensions in what is a perilously unequal country.

As with all wars, the starkest toll of Chechnya’s are the dead, who as well as the slaughtered Chechens officially include around 10,000 federal troops, and unofficially many more. Then there are the tens of thousands of injured, such as Dima, who lives with his parents in a grotty apartment on the outskirts of Moscow. In December 1999, Dima was shot in the chest in the village of Alkhan-Yurt. He heard the air rushing out of his lungs; then he was wounded again. He lay bleeding, eating snow, and preparing to die, but lived after a doctor bet his colleagues two bottles of vodka that he could be saved. Two pieces of shrapnel stayed in his back. “I lost my health forever when I was 20,” says Dima, who was incapacitated for two years; terrible years, says his mother. Alkhan-Yurt, meanwhile, became infamous for the butchery and rape committed there by the Russians soon afterwards.

Still, Dima, now at college, is relatively lucky. Many of the 1m-plus Chechnya veterans came back alcoholic, unemployable and anti-social, suffering what soon became known as “the Chechen syndrome”. This widespread experience of army mistreatment and no-limits warfare has contributed to Russia’s extraordinary level of violent crime: the murder rate is 20 times western Europe’s. But the cruelty is also reproducing itself in a less well-known and more organised way.

As well as the army, thousands of policemen across Russia have served in Chechnya. Many return with disciplinary and psychological problems, says Tanya Lokshina of Demos, a human-rights group. They also bring back extreme tactics that they proceed to apply at home, such as the sorts of cordons and mass detentions deployed against peaceful protesters in Moscow and St Petersburg in April. Torture, concluded a recent report by Amnesty International, is endemic among Russian police. It is often used to extract confessions, but not always: a survey by Russian researchers found that most victims of police violence thought it had been perpetrated for fun.

Tail wags dog

Is the war truly over, as the Kremlin says it is? Despite the loss of most of their leaders—and somewhat incredibly, considering Chechnya’s tiny size—an unknown number of insurgents are still fighting for what they call the Islamic republic of Ichkeria. They are still killing the local forces, under Mr Kadyrov, to whom most of the fighting has been outsourced. But Russians are still dying too.

So are Chechen civilians. Grigory Shvedov, of Caucasian Knot, an independent news service, says the number of “disappearances” has fallen dramatically in the past few years; but they still happen with scandalous frequency. The Council of Europe has repeatedly rebuked Mr Kadyrov and Russia over persistent torture and illegal detention. The decade of trauma, says a Chechen psychologist, has resulted in a spike in suicides, especially of people in their 30s whose lives have been derailed.

In Grozny’s Kadyrov Square a young man complains that there is no work outside the government and security services. It is an open secret that Mr Kadyrov’s reconstruction push is funded through extorted contributions from those lucky enough to have jobs. The vast sums sent by Moscow for the purpose have largely vanished into thin air.

And instability and violence have skipped across Chechnya’s borders to the neighbouring north Caucasus republics, themselves cursed by poverty, ethnic tensions and government that is bad even by Russian standards. The grimmest is Ingushetia, where Husen Mutaliyev was once a used-car salesman and father of a baby girl. Since a spell learning Arabic in Egypt, says his brother Hasan, the police had harassed Husen. Early on March 15th, Hasan says, around 20 masked men seized Husen from his house. “We are Putin’s soldiers,” was all they offered by way of identification. They beat him, then shot him when he tried to escape. His body was returned the next day. Around 15,000 Chechen refugees are still living squalidly in Ingushetia, in train wagons, warehouses and goods containers. Some are still afraid; some have nothing left in Chechnya to go back to.

One fear is that the local resentments such treatment provokes could eventually join up into a pan-Caucasian insurgency, intensified by the radical Islam that the wars have helped to foster. The biggest risk, however, may be Mr Kadyrov himself. At 30, he is ruler of what Dmitri Trenin of the Carnegie Moscow Centre describes as a “medieval khanate”, within a country that is still more an empire than a modern state. He has appointed a regional government comprised largely of ex-rebels like himself. If he lives—and for all their theatrical obeisance, some of Chechnya’s other strongmen loathe him, as do many Russian officers—what more might he want?

Mr Putin, his partner and patron, is due to leave office in 2008. Mr Kadyrov is already testing the limits of his authority; though Moscow denies it, his men sometimes scuffle with federal troops. One day, it might even suit the Kremlin to encourage this truculence. For now, it needs a stable Chechnya to reassure Russians ahead of next year’s presidential election; in the future, it might again need an unstable one.

Like his own political career, the country Mr Putin will bequeath has been formed by its long, coarsening Chechen misadventure. Mr Putin’s Russia has become a sort of tamer version of Mr Kadyrov’s Chechnya. In both, improvements in living standards have won the approval of populations who have come to expect tragically little from their leaders—a mended window, say, or a pension that is paid on time. But government in both rests on power rather than the law, and has oppressed too many while improving the lot of most. The big question for Russia, Chechnya and the world is whether the symbiotic reigns of the Chechen warlord and the Russian spook are necessary codas to tumultuous times, or the incubators of yet more instability and pain.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018