Stig Bergling, a Cold War Spy Known for His Escape, Dies at 77

Margalit Fox / New York Times

5 فبراير 2015

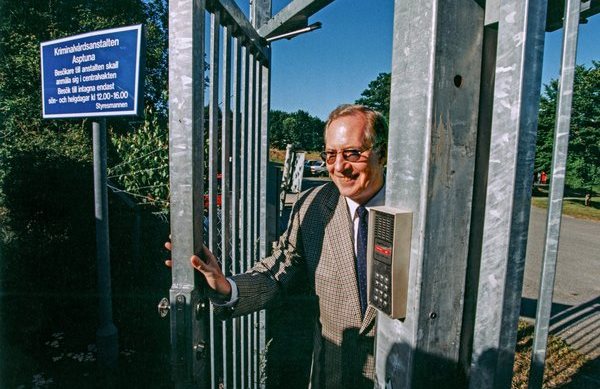

Stig Bergling, one of Sweden’s most notorious Cold War spies, who in 1987 escaped from prison during a conjugal visit, died on Jan. 24 in Stockholm. He was 77.

No cause was announced, The Associated Press reported. Mr. Bergling, who died in a nursing home, had been ill with Parkinson’s disease for many years.

A former officer in Sweden’s national security police, Mr. Bergling stood trial in 1979 on charges that he had sold military secrets to the Soviet Union. Convicted that year, he was sentenced to life in prison.

What followed — including Mr. Bergling’s escape (inadvertently abetted by the Swedish authorities); an international manhunt (inadvertently abetted by the Soviets); his years on the lam amid swirling rumors of his whereabouts; and his voluntary return to Sweden, reimprisonment and later parole — was a dark absurdist farce that made headlines round the world.

Mr. Bergling’s flight from custody was a major scandal in Sweden, long known both for its progressive penal policies and its efficiency. In the wide consensus of the international news media, what made his escape possible was far too much of one and far too little of the other.

Stig Eugen Bergling was born in Stockholm in 1937 to a middle-class family: His father was in the insurance business; his mother was a secretary. In the late 1950s he became a policeman; a decade later he was appointed to the security police, an intelligence agency whose duties include counterespionage and counterterrorism.

Mr. Bergling’s job gave him access to some of Sweden’s most sensitive military documents, and in the 1970s he was alleged to have sold nearly 15,000 of them to the Soviets. It was avarice, not ideology, he later said, that turned him to espionage.

In 1979 Mr. Bergling was arrested in Tel Aviv and extradited to Sweden. At trial, there emerged a narrative of spycraft that in its 20th-century sensibilities — microdots, radio communications, letters in invisible ink — now seems almost quaint.

Though he was given a life sentence, under Sweden’s penal laws, which stress rehabilitation rather than punishment, Mr. Bergling might well have been paroled after about 15 years.

In 1986, while serving his sentence in Norrkoping, in eastern Sweden, Mr. Bergling married a longtime friend, Elisabeth Sandberg. Over the next year he was granted a series of conjugal visits at her apartment in a Stockholm suburb, including one in 1987 for which the couple planned very carefully.

That autumn, Mr. Bergling’s wife rented several automobiles under her name and took out a bank loan of some $12,000. The Swedish authorities had already unwittingly furthered the couple’s plans by allowing Mr. Bergling — who said he hoped for eventual parole and a fresh start afterward — to change his name to Eugen Sandberg. According to news reports, they also issued him a new passport in that name.

On the evening of Oct. 6, 1987, an unarmed guard escorted Mr. Bergling to his wife’s home for a routine conjugal visit. In the interest of propriety, the guard repaired to a nearby hotel for the night.

On Oct. 7, when the guard called at the apartment, the couple were nowhere to be found. As Mr. Bergling described it afterward, they had stolen out the back door early that morning, disguised as joggers, availed themselves of at least one of the waiting cars, made for Finland and from there traveled to the Soviet Union.

It took more than 10 hours before the Swedish authorities issued an official alert for Mr. Bergling, partly because they seemed confused, according to news reports, about which name to search for. But by then he had crossed the border, undetected, as Eugen Sandberg.

An international furor ensued. On Oct. 19, Sten Wickbom, the Swedish justice minister, resigned over the escape.

For the next seven years, with police forces in 70 countries alerted to their flight, Mr. Bergling and his wife were reported to have roamed throughout Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Amid a welter of rumors — among them that he had undergone plastic surgery and was ensconced in Vienna, selling real estate — they eluded their pursuers.

In February 1991, with the fugitives still at large, a Swedish television station wrote to the Soviet authorities, alerting them to the suspected presence in their country of an escaped Swedish criminal named Eugen Sandberg. (The letter failed to mention the precise nature of his crimes.)

Believing Mr. Sandberg to be a garden-variety crook, the Soviet interior minister obligingly took to the airwaves, exhorting the public to search for him. But this, too, proved of no avail.

In 1994, saying they were homesick for their families, Mr. Bergling and his wife returned to Sweden of their own accord. Mr. Bergling was returned to prison; his wife, who was not charged, died of cancer in 1997.

Mr. Bergling, who was paroled on medical grounds that year, is believed to have been married and divorced at least once more; information on survivors could not be confirmed. In recent years he had lived under the surname Sydholt.

In the wake of Mr. Bergling’s arrest, Sweden was forced to reorganize its defense and security operations at an estimated cost of $45 million, United Press International reported in 1987. By all accounts the cost of his flight in terms of international embarrassment was also considerable.

“Apart from actually giving him a ticket to Moscow,” an unnamed Swedish official told the Australian newspaper The Courier-Mail in 1987, “there was not much more we could have done.”

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018