The Arab Spring vs. development

Dima El Hassan /The Daily Star

16 أكتوبر 2014

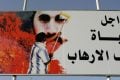

No wonder that the so-called Arab Spring nations are currently undergoing a crucial phase with the rates of violence, destruction, emigration and instability escalating. All of these impose on us challenges that are difficult to confront. Now the entire world is concerned about what is happening here and is working to shift the development process at the international and regional levels in an attempt to prevent the impact of the disturbances from spreading worldwide. Nonetheless, given the accumulated experiences with the “planners of development,” we need to build a strong awareness on development to find ways to compromise between what we really want and what we can do in order to be able to achieve the prosperity that we aspire for our societies. For that, we may need to go back to the essence to understand how the development mentality has evolved globally in response to the emerging realities shaping our history. Going back to the roots can be an essential step in shaping the future that we want, rather than the one others want.What is development? Why are powerful authorities always rushing to dictate development to the less powerful and the so-called poor? Why are so many countries eternally doomed with “getting developed?” How can one assess the need and impact of development?

Prior to 1949, the notion of development was commonly linked to income growth per capita. This is also reflected in the U.N. Charter (1947). However, the story of development in its broader sense begins, according to the Development Dictionary, when U.S. President Harry S. Truman, in his inaugural speech on Jan. 20, 1949, for the first time declared the Southern Hemisphere as “underdeveloped areas.” On that day, 2 billion people became “underdeveloped.” Hence, they stopped being what they were, in all their diversity, distinctiveness, cultural and historical backgrounds and were transformed into an “inverted mirror of others’ reality”: a mirror that degrades them and puts them at the end of the line.

The focus turned toward the probable factors behind this “underdevelopment”: imbalanced exchange, dependency, trade barriers, corruption, lack of democracy, etc. Accordingly, the main reason behind the underdevelopment of countries was the process of colonization. Hence, “underdevelopment” led to the creation of “development.”

In the late 1970s and early 1980s development considerations were overtaken by the debt crisis of the so-called “less-developed countries.” In 1974, the COCOYOC Declaration called for a focus on human development, rather than the development of things.

The human aspect of development derived from the experience of the newly developed countries (such as East Asia). But it’s also true that some countries that succeeded in spreading education among their labor force (like Sri Lanka) haven’t managed to realize much economic progress, indicating that capital investment may not be sufficient for sustained economic growth. Another major shift in development thinking stemmed from the experience of the industrialized countries themselves (like the U.S.), showing that economic growth could be coupled with social problems such as income distribution disparities, homelessness, breakdown of family ties, environmental pollution, crimes and drug abuse.

In the late 1970s, UNESCO promoted the “endogenous development” after realizing the impossibility of imposing industrial countries’ development models on others.

During the 1980s, with the recognition of environmental degradation, the notion of sustainable development emerged as a form of development satisfying the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

In 1990, the first Human Development Report defined human development as the process of widening people’s choices, introducing the Human Development Index as a new measure of development adding indicators as education and health to the simple per capita income.

A record of world summits followed in the 1990s bringing political and international commitments on issues related to education, children, environment, women, population and social development.

Throughout the decades the concept of development took many drifts. It has surely surpassed its pure economic dimension to focus more on the human aspect and enhancement of the well-being, putting the individual as both the ultimate goal and the most important means to development.

I just gave this quick review so that we can consider together why development has become a permanent rather than temporary state to nations labeled as “developing” or “underdeveloped?”

While we expect countries with sufficient natural resources to have successful economies by using or selling them to enhance their own growth, many (in the Middle East, Asia and South America) have massive supplies but are still struggling economically. Others (like Japan and Singapore) with sparse resources boast strong economies.

The education of skilled labor could be another factor for success, through its impact on generating better incomes and employment opportunities. Yet there are many countries with highly educated people that are still economically weak (like Lebanon).

An interesting review of “Why Nations Fail” (written by MIT economist Daron Acemoglu and Harvard political scientist James Robinson), argues that having abundant natural resources and an educated labor force may not be enough for a sustained growth. The main reason behind the poverty gap between nations lies in the role of political and legal institutions.

Politically, nations must be inclusive by embracing competition and change. Legally, successful nations must have legal bodies protecting ownership, guaranteeing that those doing the work earn the benefits and not the ruling elite, be it political or economic. This was the case behind the success of England upon the industrial revolution and the failure of countries that developed after the Ottoman Empire. The revolution of the Arab Spring countries is still in question based on whether it will produce the needed shift toward inclusiveness or another new elite will replace the old one, signifying the “iron law of oligarchy.”

Above all, I believe stability is the key for any society to prove itself successful. There is also no recipe for development. It has to come from and by the people themselves, through their own empowerment and inclusiveness in the process of developing their own society.

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

عن أمل جنبلاط المتجدد: لبنان يستحق النضال

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

صحافيون أم عرّافون!

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

ماذا يجري داخل أروقة بيت الكتائب المركزي؟

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

عن الخرائط التي تُرسم والإتفاقات التي تتساقط!

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

“الإنحراف في الحياة”/ بقلم كمال جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

هاشتاغ #صار_الوقت يحل أولاً في حلقة جنبلاط

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

طاولة نقاش عن أزمة الصحافة في جامعة AUST

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: ليظهر لنا وزير مكافحة الفساد حرصه في صفقات البواخر والفيول

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

عبدالله: غريب أمر وزارة مكافحة الفساد!

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

Comment to Uri Avnery: How Sad What Is Looming Ahead

“Not Enough!”

“Not Enough!”

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

… لمن لم يقرأ يوسف البعيني/ بقلم وسام شيّا

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

كمال جنبلاط في مولده الأول بعد المائة: تعاليمه وأفكاره ما زالت الحلّ/بقلم عزيز المتني

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

رئيس حزب/ وليس (… سابقاً)/ بقلم د. خليل احمد خليل

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

التوازن السياسي في لبنان

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

لبنان… مشاريع انقلابية مؤجلة

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

جنبلاط وحَمَلة أختام الكاوتشوك

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Le Liban est un symbole de tolérance

Our Automated Future

Our Automated Future

The True Origins of ISIS

The True Origins of ISIS

Les Misérables vs. Macron

Les Misérables vs. Macron

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

عذراً أيها المعلم/ بقلم مهج شعبان

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

رساله الى المعلم / بقلم ابو عاصم

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

إلى روح القائد والمعلم كمال جنبلاط/ بقلم أنور الدبيسي

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018

أسرار وعناوين الصحف ليوم الجمعة 14 كانون الاول 2018